02/20/2020

Far From Russia, A Place To Be Comfortably Russian

- Share This Story

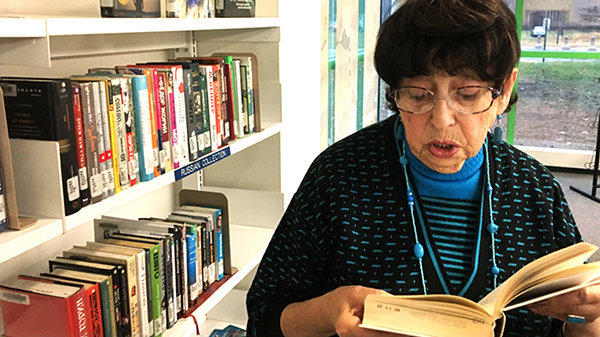

Irina Parkman reads from a book in the Russian collection at Cleveland Public Library's Memorial Nottingham Branch. [Justin Glanville / ideastream]

Article reprinted with permission from ideastream.

By: JUSTIN GLANVILLE | ideastream

In the early 1990s, Irina Parkman was living in Nizhny Novrogod, a city in western Russia. It was a proud place, she says, with a grand, red-brick kremlin — even its own regional anthem.

"It’s a very big city that was founded in 1221, meaning as old as Moscow," she said, speaking in Russian. "It’s the place of two very famous rivers, the Volga and Oka."

The kremlin in Nizhny Novrogod. [Wikimedia Commons]

Irina’s husband, German (pronounced Her-man), worked as a computer programmer at the Gorky Automobile Factory. But in those waning days of the Soviet Union, Parkman said, life was tough. German wasn’t paid much, for one. And even worse, they both felt pressure to change who they were.

"My husband and I didn’t want to be members of the Communist Party," she said. "We weren’t Communists. Many times people told him, 'Not only are you Jewish, but you don’t even want to become a Communist? You’re cutting your career short.' But he said, 'I’m not a lifer.'"

Looking For A New Start

The family dreamt of moving to the United States. But for years, dream was all they could do.

"In our factory, they didn’t only make cars, they made military equipment," Parkman says. "Because of that, we had a closed city."

The Volga, a car model produced at the Gorky Automobile Plant in Nizhny Novrogod. [Wikimedia Commons]

After the Soviet Union formally dissolved at the end of 1991, the rules loosened. Parkman and her family applied for permission to leave. In 1992, permission was finally granted. It was the beginning a stream of immigration from the former Soviet Union to Cleveland and other U.S. cities.

The Parkmans flew to the United States with what they could carry in their arms. Everything else they left behind.

An Unexpected Turn

Irina couldn’t have known it at the time, but it was a move that ended up saving her husband’s life. Three years after they settled in Cleveland, German had a doctor’s appointment.

"He had cancer," she said. "They found it on a Friday. On Monday, they still hadn’t let him out of the hospital; they performed surgery. Can you believe it? In three days. They were worried that it was already too late."

It wasn’t too late, though. He survived the surgery and made a full recovery — something she attributes to the quality of U.S. healthcare.

The couple were in their early 60s by then, and took German’s medical scare as a sign to slow down and enjoy life more. In another twist neither of them could have predicted, they ended up doing that by going back to the place where they’d felt like such outsiders in the past. To Russia.

Or at least, the local version of Russia.

Russia in Cleveland

Irina and German became familiar faces on Cleveland’s busy circuit of Russian-American cultural events, dinners and lectures – including one of the focal points on that circuit: the Memorial Nottingham branch of the Cleveland Public Library, in the city’s northeast corner, near Euclid Beach.

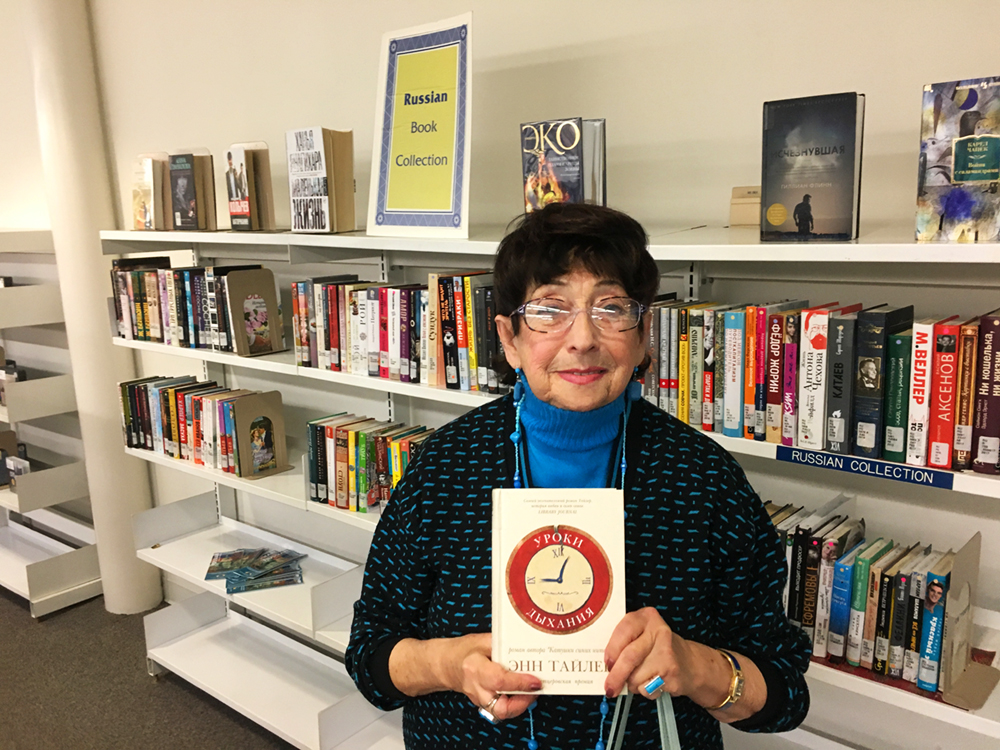

On a chilly winter afternoon, Parkman — now 85, and wearing her trademark blue necklace and turtleneck — stands in front of the wall of books that serves as the “Russian Book Collection” with bilingual librarian Victoria Kabo.

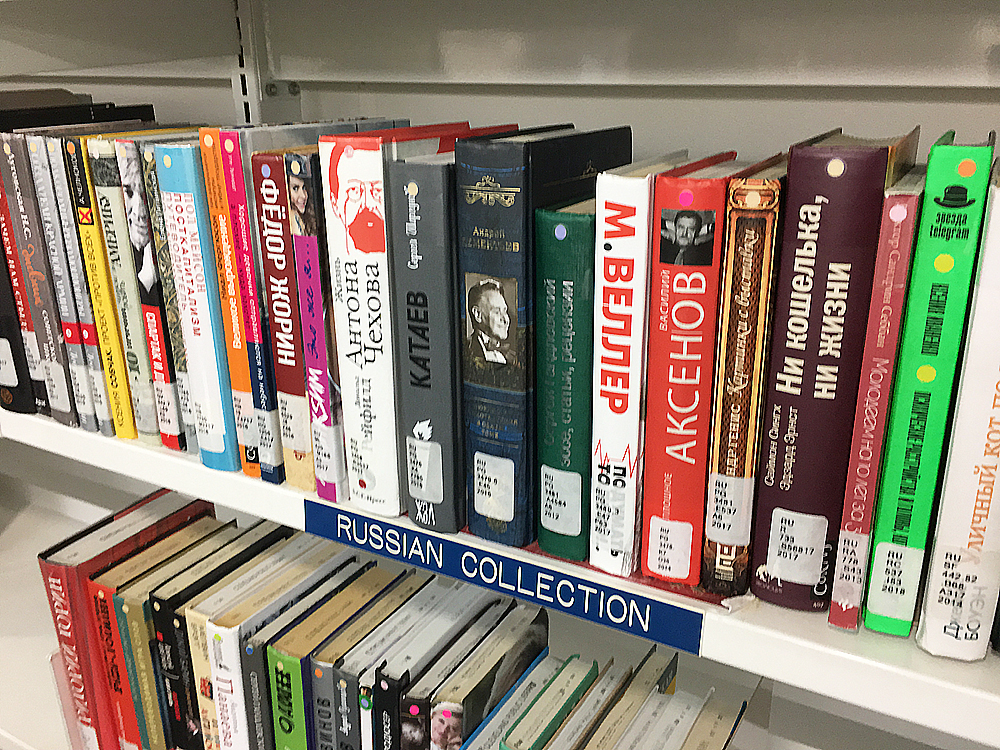

The Russian Collection at Memorial Nottingham Library serves a nearby population of Russian speakers. [Justin Glanville / ideastream]

Kabo is one of several employees here who can speak Russian or Ukrainian with the growing population of immigrants who live nearby.

Memorial Nottingham library became a combination university and social club for her and German, she says. To describe its meaning for her, she briefly switches to English.

"This library, we very happy," she says, before going back to Russian. "We learn so much here. We meet other Russians of equal intelligence, discuss the books, sometimes disagree. But, on the whole, we have very good interactions."

Irina Parkman holds up a recent favorite: a Russian translation of Anne Tyler's "Breathing Lessons." [Justin Glanville / ideastream]

German died a few years ago, 10 years after his cancer treatment.

But Irina still comes as much as she’s able.

This unassuming building, half a world away from the banks of the Volga, represents something important for her: a place she and German could be both Russian — and themselves.

This story is part of ideastream's ongoing collaboration with the Cleveland Public Library to present a "snapshot" of Cleveland and Clevelanders in 2020.

Special thanks to Victoria Kabo of Cleveland Public Library for collecting the original interview for this story, and to ideastream's Mike Shafarenko for translation help. You can hear the full audio interview here.